Playwright Alan Pollock reflects on another night to remember - taken from the programme for the 2013 production

Twelve years after making its debut at the Belgrade Theatre, Alan Pollock‘s breathtaking wartime drama One Night in November continues to resonate powerfully with Coventry audiences.

Telling the story of one family’s experiences of the Coventry Blitz, the play was revived three times after its 2008 premiere, with each production warmly received by audiences and critics alike.

This year is the 80th anniversary of the terrible night when bombs fell on the city, and to mark the occasion, we’re making the most recent staging of the show available to stream via our website from 14-30 November.

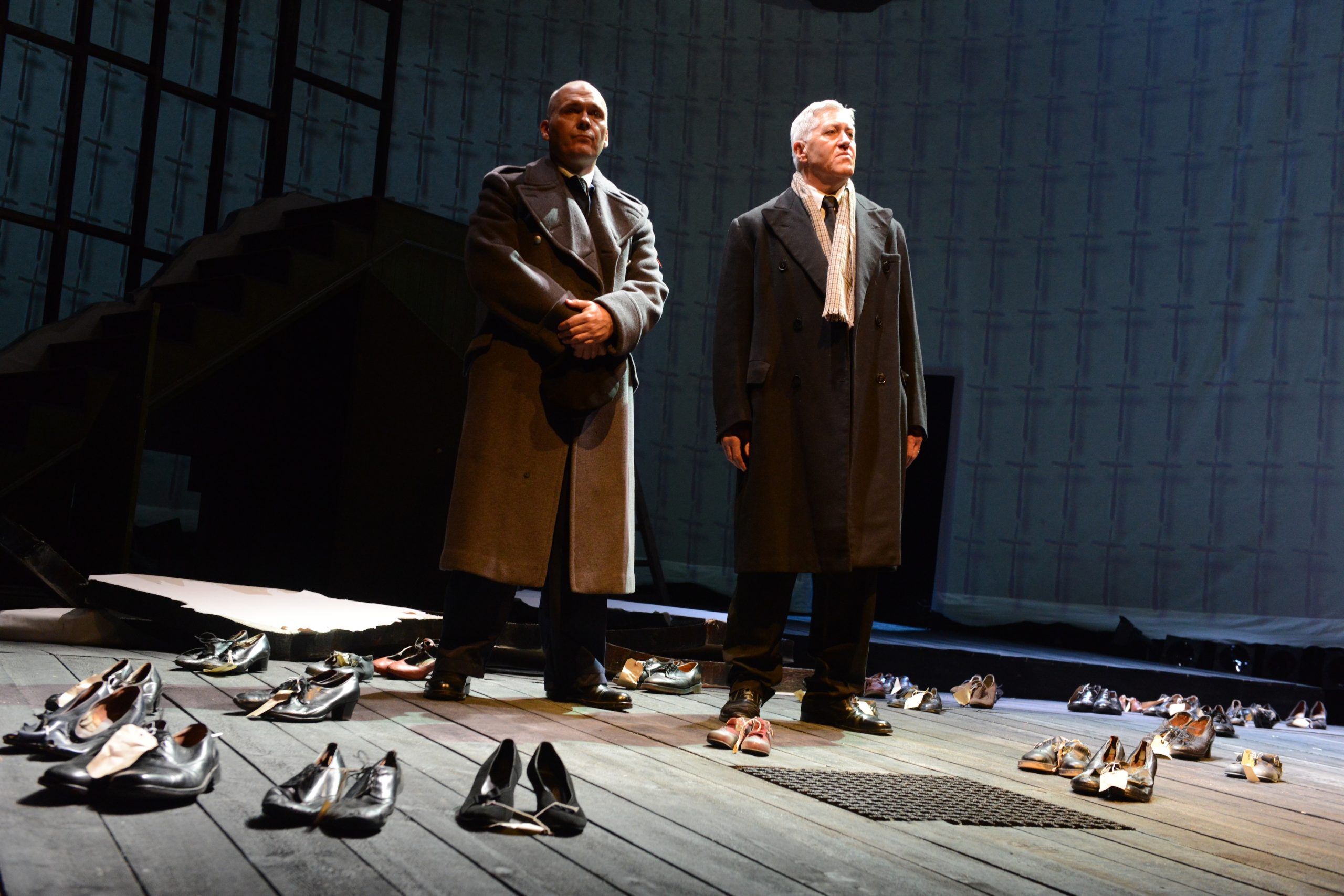

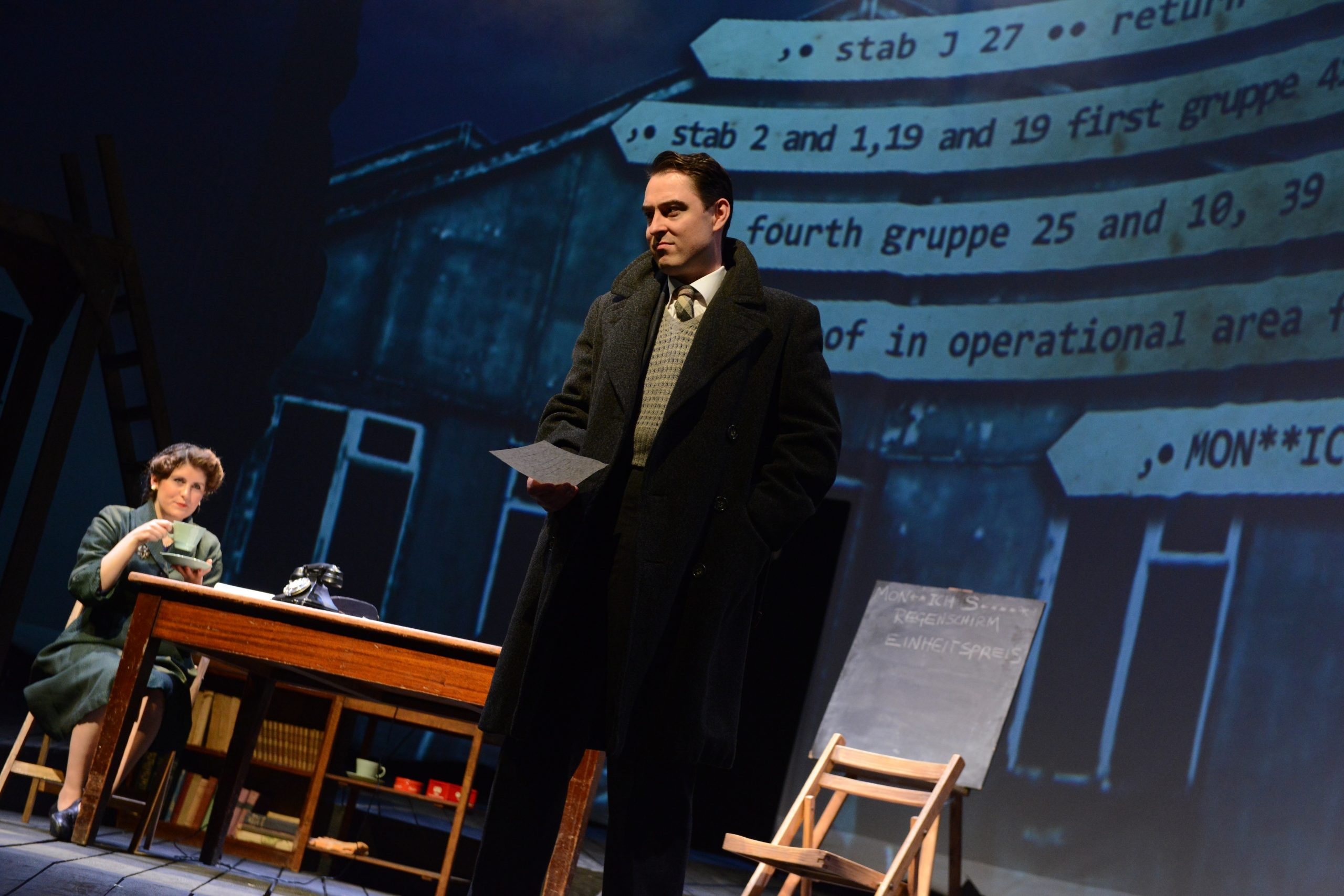

Filmed in 2013, the production stars Charlotte Ritchie (Call the Midwife, Ghosts) as Katie Stanley, and was directed by Belgrade Theatre Artistic Director Hamish Glen. Ahead of its release online, we took a look back at an interview with Alan Pollock, written by Michael Davies for the One Night in November programme.

MD: Where did the inspiration come from for One Night in November?

AP: I remember an English lesson when I was about twelve or thirteen – this would be about 1975 – and the first wave of books was starting to be published which discussed the whole Bletchley thing and how that secret had been kept for 35 years. That was astonishing – can you imagine that now? The teacher at the time said Coventry may have been sacrificed as part of the greater effort. That lodged in my mind. In the mid-2000s, I found myself coming back to Coventry more and more, as my parents never moved away, and I was wandering around the city thinking, how did it come to look like this? Then the story came to me: what if somebody in Bletchley knew in advance about the raid? What if you had a secret that you couldn’t tell? That’s what makes the story work, I think.

MD: A lot of the themes – secrecy in the national interest, personal moral dilemmas in the face of government demands – seem particularly current. Has your sense of the play shifted at all in the light of recent news items about Wikileaks, Edward Snowden, The Guardian and so on?

AP: It’s not something I’d actually thought of but there is definitely a resonance there. What constitutes the national interest is very different in war to peace. Certainly what’s changed is who gets to decide what the national interest is. Clearly the world has changed in loads of ways. Communication has changed, notions of patriotism have changed. We are at war on several fronts, though you would never know that from reading newspapers.

MD: The play uses a very personal, human story to illuminate the bigger issues. Was that a deliberate choice?

AP: What gives the play its torque is the thing that Michael’s superior says to him: the penalty for revealing secrets is still death. It’s a hugely risky thing he does, coming to Coventry. Why he does come is never fully apparent to the family and that drives him mad.

MD: What research did you undertake?

AP: I talked to three or four people who’d experienced it at first hand but it’s harder than you think because remarkably few people have been in Coventry for more than two or three generations. Then there is a welter of printed stuff with lots of verbatim reports.

MD: Why do you think One Night in November has had such a powerful effect on Coventry audiences?

AP: Part of the anger, the hurt that people feel still – and this was stirred up when the play was first on – is the idea that Coventry was expendable. The issue isn’t ‘Did Churchill know or didn’t he?’, it’s why he did what he did. And within a year, the Americans entered the war after Pearl Harbour.

MD: So you’re convinced Churchill knew of the air raid in advance and could have acted to protect the city?

AP: Churchill knew about it by three o’clock that afternoon. Most of the damage that night came from incendiary bombs, and the auxiliary fire services had to come from Stafford and places like that, so a quiet word to lay on extra resources could have made a huge difference without tipping anyone off about the Enigma code being cracked. I don’t really understand why the Churchill camp can’t admit that he might have made that decision. He was absolutely the man for the situation but it’s not like he didn’t have form in this area, and in war you make tough decisions.

MD: What’s your working relationship like with Hamish Glen?

AP: We just kind of understand one another. I did know him vaguely – when I worked in Scotland, at the Traverse Theatre, he was at the Tron – so our paths had crossed. I just said to him, this is a story I have always wanted to tell, are you interested? He said yes, although it took a while to research and develop it. He helped me to focus in around the love story. What he’s good at is drawing out the detail through the drafts. I think we have quite similar personalities – we both like popular, accessible stories.

MD: The play has had a terrific impact on audiences, with many in tears and deeply moved. That must be pleasing for you as a playwright?

AP: Unless plays hit you in the guts and in the heart you’re wasting your time. That’s been the single most satisfying aspect for me: writing this play and seeing it have this extraordinary effect on people. Hamish says it’s the most direct impact on an audience he’s ever seen, and the degree to which that has happened has been humbling.

MD: Has the play changed this time?

AP: It’s been rethought for this production. When we went from B2 to the Main Stage in 2010 there were big gains from moving to a big stage but it’s possible that some of the more intimate, intense moments had to be sacrificed. The Main Stage show was awesome, but I think Hamish has worked hard this time on finding that intensity again. When the bombs went off in that first production in B2, the effect was extraordinary. I’m enormously grateful to Hamish for the productions he’s given the play, and to see it revived again is very exciting for me.

© John Good

One Night in November will be available to watch online from 14-30 November 2020. Tickets are available to book now. Please note that box office phone lines remain closed while staff continue to work remotely.